Oct 01 Mental health services are lacking in rural counties around Pittsburgh

Rural county residents and providers say the problem doesn’t come with easy — or cheap — solutions.

NEXTpittsburgh – Indiana County resident Pamella Clouser describes the county’s mental health care services with two words: oversubscribed and execrable.

“There are not nearly enough mental health care personnel for this county — not even remotely,” she says. “If you need to see a psychiatrist, they’re booking months out.”

Clouser found her therapist because her primary care physician had the foresight to connect her with one during an emergency appointment. She’s been seeing the same therapist since 2014.

But Clouser attributes that success to her middle- to upper-middle-class socioeconomic status in her rural borough. If she and her husband had a different doctor — or none at all — she wouldn’t have been afforded the same care.

“We’re both very educated, both familiar with medical stuff, and it is a giant pain in the tokus to navigate our medical care,” Clouser says. “Somebody who doesn’t have that level of education, somebody who doesn’t have the resources to go to Pittsburgh if you need to get in sooner, somebody who is overwhelmed with everything that you need to do to basically keep body and soul together isn’t going to have the bandwidth to be able to navigate that.”

Securing appointments with psychiatrists in rural counties is even harder. They’re fewer and further between in her area. After booking an appointment for their daughter three months in advance, the Clousers arrived to find the doctor was on a lengthy vacation. They hadn’t received advanced notice.

Office administrators offered to rebook, but it would be an additional 14-week wait. “For a child that needed psychiatric care, and there was no other option offered or available,” Clouser recalls.

Based on her experiences with rural psychiatrists, Clouser says she thinks some who work in rural Pennsylvania are hesitant to prescribe controlled substances because of the region’s reputation of opioid addiction.

“I know clinicians can only do so much in a day; they are not Superman,” Clouser says. “But when you combine the waiting with the office staff and then clinicians that are maybe focused on other stuff than actual mental health help, it’ll discourage you from trying again.”

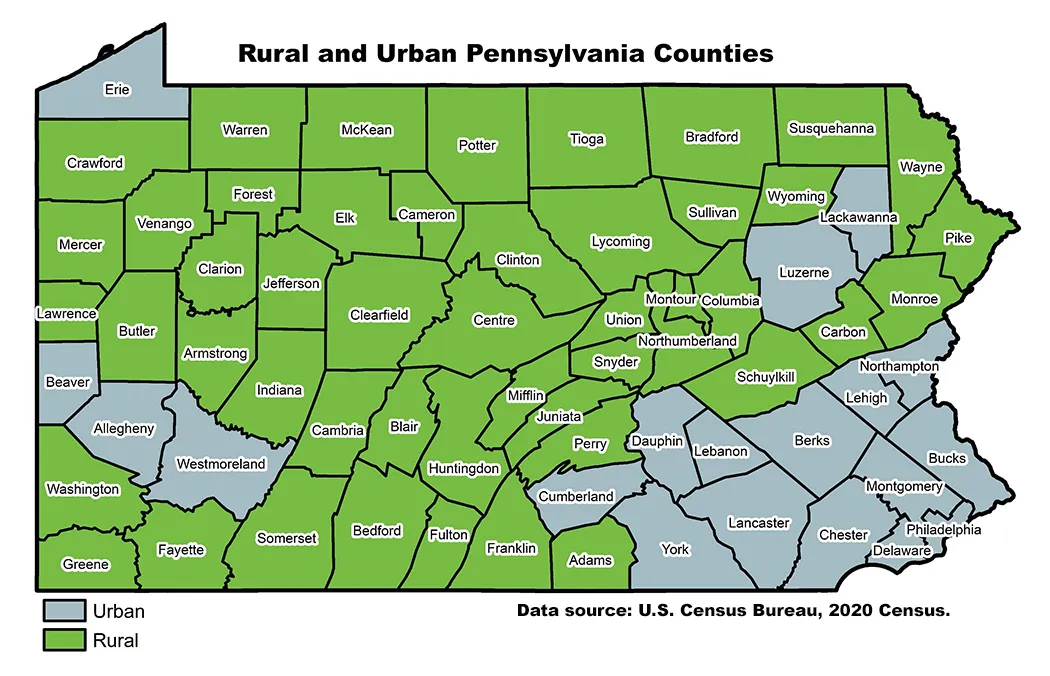

In the United States, 70% of rural areas don’t have access to a psychiatrist. Only five of Pennsylvania’s 35 psychiatric hospitals are in rural areas. Of the commonwealth’s 48 counties, 44 were classified as having a “whole county shortage” of mental health professionals.

Jim Sharp, chief operating officer and director of mental health for Rehabilitative & Community Providers Association, listed these and other shortcomings of Pennsylvania’s mental health care system as the keynote speaker at the Staunton Farm Foundation’s biannual Rural Behavioral Health Conference in Cranberry on Thursday, Sept. 25.

“How do we move forward?” Sharp asks a crowd of over 100 providers and administrators. “There needs to be a significant focus on the workforce, the programming, and it will take a long-term commitment.”

Staunton Farm Foundation supports mental health service providers in Allegheny, Armstrong, Beaver, Butler, Fayette, Greene, Indiana, Lawrence, Washington and Westmoreland counties through grantmaking and advocacy.

Executive Director Monique Jackson says the 2025 conference addressed policy changes, budget issues and service gaps that prevent rural residents from receiving care.

“Allegheny County is resource rich, and oftentimes, our rural partners have less resources, including funding,” Jackson says. “This is our opportunity to level the playing field by giving them information that our urban friends in Allegheny County get.”

Robert Hamilton, director of human services with Westmoreland County Department of Human Services and a conference attendee, tells NEXTpittsburgh that a problem that looms larger than receiving help is knowing where and how to start.

The claim comes with personal investment. Hamilton was injured during military service and was prescribed narcotics. In the years after his service, he faced addiction and homelessness with little recourse.

“It took me years to get clean because every time I had that moment of clarity where I wanted to, I couldn’t access services — I couldn’t get anything,” Hamilton says.

It took an arrest and the threat of incarceration for the pathway to mental health and substance abuse services to materialize for Hamilton. Similar to Clouser’s physician, Hamilton met a police officer who connected him with the resources he needed.

“If it wasn’t for that certain officer, I never would have; any other officer may have locked me away and I would have never gotten the lifesaving services that I needed,” he says. “I would have just went and did time and got out and started using again.”

Now, Hamilton’s an advocate for getting boots on the ground and aggressively spreading information about mental health and substance abuse services throughout rural communities.

“You shouldn’t be lucky to get recovery. You shouldn’t be lucky to stumble into those services.”

While workforce growth and access improvements were key conversation points at the Rural Behavioral Health Conference, its speakers and attendees didn’t have clear solutions to the many issues facing the industry. Lunch-hour sessions asked providers and administrators to spitball solutions.

To Clouser, one way to solve the problem would be the expansion of a service like UPMC’s resolve Crisis Services, which offers a walk-in crisis clinic, teletherapy and mobile clinics to Allegheny County residents through Western Psychiatric Hospital.

One conference panel discussed the roles libraries might play as locations for therapeutic services. Since many are already marketed as community hubs, they could prove a nearby and neutral place for appointments in rural communities.

But any such addition to or expansion of service relies on funding.

During Sharp’s keynote, he called out Pennsylvania’s ongoing budget delays. According to reporting by the Pennsylvania Capital-Star, funding earmarked for human services and safety nets like senior services, drug and alcohol programs, child welfare services and health departments are being held up until its approval.

“Our state organizations are hampered by the very rules that they pass,” Sharp says. “We have a bipartisan legislature that cannot pass the state budget, and funders and funding systems who sometimes don’t see the big picture.”

Whether it was about budget concerns, staffing or access to services, the uncertainty felt by Hamilton and Clouser was all too familiar to providers at the conference. It was pervasive throughout Sharp’s address.

“Stay optimistic,” he said in closing. “I know it’s going to be hard.”